What Is the Roadmap of Semiconductor Technology for Mining?

Bitcoin mining hardware has advanced rapidly with each chip shrink. Let’s look at how far we’ve come—from early large-node ASICs to today’s cutting-edge chips, and what’s next.

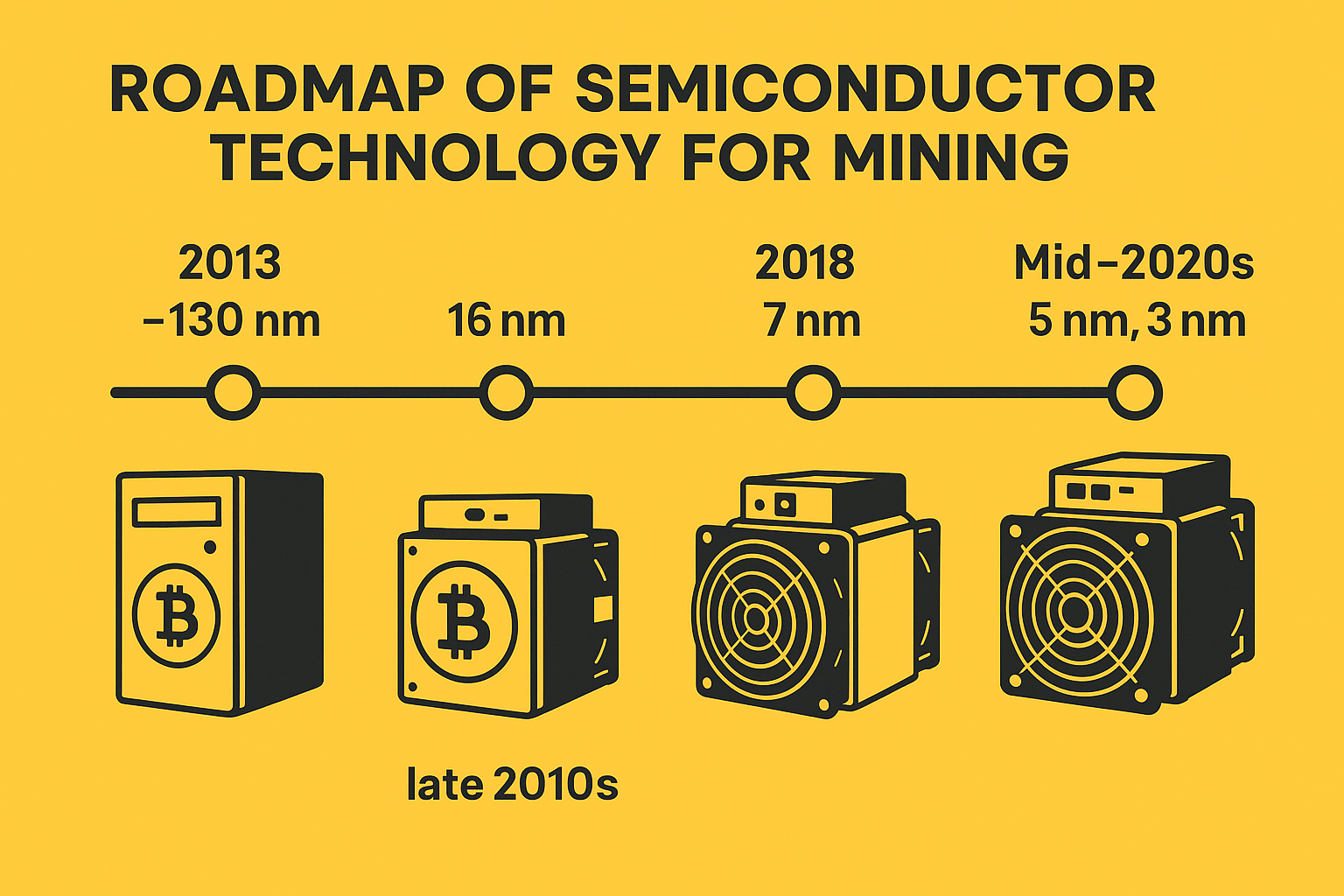

Bitcoin mining ASICs have steadily moved to smaller chip nodes over the years. Early miners in 2013 used ~130nm chips, shrinking to ~7nm by the late 2010s. Today’s cutting-edge machines run on 5nm or 3nm chips (with 2nm on the horizon), each generation boosting efficiency.

The evolution of mining chips has been a race of constant miniaturization. In 2013, the first Bitcoin ASICs were produced on a 130 nm process. Within just a few years, manufacturers jumped to 28 nm and then 16 nm nodes, dramatically improving performance and energy efficiency. By 2018, miners like the Antminer series had adopted 7 nm chips, and soon after that 5 nm designs entered the scene. Now, in the mid-2020s, companies are introducing 3 nm chips in top-tier machines. (I remember deploying the Antminer S9 on a 16 nm node in 2016—it was amazing to see it outperform older 28 nm machines by a huge margin.)

To put this in perspective, here’s a brief timeline of ASIC chip nodes in Bitcoin mining:

ASIC Node Progression Timeline

| Process Node | Year (approx) | Notable Miner Example |

|---|---|---|

| 130 nm | 2013 | First-gen ASIC miners (e.g., Canaan/Avalon) |

| 28 nm | 2014–2015 | BitFury & other early ASICs |

| 16 nm | 2016 | Antminer S9 (Bitmain) |

| 7 nm | 2018–2019 | Antminer S15/S17; WhatsMiner M20 series |

| 5 nm | 2021–2022 | Antminer S19 XP; WhatsMiner M50 |

| 3 nm | 2024–2025 | Antminer S21 (latest generation ASICs) |

| 2 nm | ~2025–2026 | Projected next-gen miners |

Each new node brought a big leap in how many hashes per second a chip could do per watt of power. For example, early 130 nm devices had very low efficiency (hundreds or thousands of Joules per terahash), whereas a modern 5 nm or 3 nm miner might use only ~20 J/TH or less. This means newer machines produce the same hashrate while consuming a tiny fraction of the electricity required by older ones. The impact on mining profitability has been profound: operations that upgrade to the latest chips can hash more for the same power, outcompeting those with legacy hardware.

Today, we stand at the threshold of the 2 nm era. Foundries like TSMC plan to ramp up 2 nm production by 2025, and mining manufacturers will undoubtedly follow suit, integrating 2 nm chips into the next wave of ASIC rigs. This could further improve efficiency (some speculate ~10–12 J/TH for 2 nm-based miners). However, it’s worth noting that as we reach these cutting-edge nodes, the pace of improvement is slowing. In the past, a new generation often meant 50–100% efficiency gains, but recent jumps are closer to 20–30%. Shrinking from 5 nm to 3 nm, for instance, yielded a more modest boost compared to earlier leaps. We’re starting to bump against the practical limits of traditional semiconductor technology, which sets the stage for our next question.

What Are the Theoretical Limits of Silicon, and Is There Promise in New Materials?

Silicon chips kept shrinking for decades, but at some point physics pushes back. How small can silicon transistors go? This section explores where that limit lies and if new materials can break through.

Silicon transistor scaling faces a hard limit at roughly the 1 nm scale, where quantum tunneling and atomic-size effects make further shrinking impractical. To push beyond these limits, researchers are exploring new materials (like carbon nanotubes and other 2D semiconductors) that could enable continued performance gains even when silicon runs out of steam.

The phenomenal run of Moore’s Law is finally hitting a wall. Once transistor gate lengths approach just a few atoms in width (around 1 nanometer), strange things happen: electrons can quantum tunnel through the barrier even when the transistor is supposed to be “off,” and it becomes extremely difficult to control heat and leakage. In practical terms, around the 2–3 nm node, chip engineers are already seeing these quantum effects erode the benefits of further scaling. A senior technologist at ASML pointed out that quantum tunneling and atomic spacing impose fundamental limits that may constrain progress beyond the 1 nm generation. Simply put, we can’t keep halving the transistor size using silicon forever – physics won’t allow it.

So what is the smallest we could go with silicon? Many in the industry believe that somewhere around 1.0 nm (10 Ångströms) is the final feasible node for silicon-based transistors. At that scale, we’re dealing with channels only a few atoms thick. Gate-all-around transistor designs (GAAFETs) are helping us approach this by better controlling current at small geometries. And there’s even the prospect of CFETs (Complementary FETs), which stack NMOS and PMOS transistors vertically to double density. Experts anticipate that vertically stacked transistors (CFET) could extend silicon to the 1.4 nm and 1 nm nodes. But beyond that, even these advanced 3D tricks might not be enough.

This is where new materials come into play. To break the silicon barrier, researchers are experimenting with entirely different semiconductor materials that can operate at atomic scales without the same quantum problems. The IMEC technology roadmap suggests that by the time we reach ~0.2 nm (so-called “2 Angstrom” nodes) around 2037, the industry will need to switch to 2D material transistors (2DFETs). Unlike silicon, which becomes ineffective when thinned down too far, certain 2D materials can form stable, one-atom-thick transistor channels.

What are these new materials? Here are a few promising candidates being explored:

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): These are essentially rolled-up sheets of graphene forming tiny cylindrical tubes. CNTs can act as ultra-tiny transistor channels that conduct electricity with almost no resistance. They can switch at sizes below 1 nm without suffering the severe tunneling currents that plague silicon. In fact, researchers have already built prototype chips with CNT transistors. One recent achievement was a CNT-based chip that proved 1,700 times more efficient than a comparable silicon chip for certain tasks. If such technology is applied to Bitcoin mining, it could dramatically reduce energy per hash – some speculate we might see ASIC efficiencies drop below **5 J/TH** with mature CNT-based designs. As someone who spends a lot on electricity for mining, the prospect of CNT-powered miners is incredibly exciting (almost science fiction becoming reality!).

- Two-Dimensional Semiconductors: These are materials that naturally form layers only an atom or a few atoms thick. Examples include molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) or tungsten diselenide, among others. Unlike graphene, many of these 2D semiconductors do have a bandgap, which means they can function as transistors (turning current on and off). Because they are so thin, they could serve as channels in transistors at scales well below 1 nm. The idea is to use a single atomic layer as the transistor channel – this radically thin channel can help suppress leakage currents when the device is off, solving some of the quantum tunneling issues. Major chip makers and academic labs are heavily researching 2D materials now. We could see them start to appear in advanced nodes in the 2030s if all goes well.

- Graphene: Often mentioned in the same breath as future materials, graphene is a one-atom-thick sheet of carbon. It boasts phenomenal electrical conductivity and strength. However, pure graphene has no bandgap (it’s more like a metal than a semiconductor), which means a transistor made from graphene can’t switch off – a fatal flaw for logic use. Because of this, graphene by itself likely won’t be used as the channel material in transistors. That said, graphene is being investigated for interconnects or other parts of a chip, and researchers are looking at modified forms (like graphene nanoribbons or using graphene in composite with other materials) to harness its properties while introducing a bandgap.

- Gallium Nitride (GaN) and Others: GaN is a semiconductor known for its high electron mobility and is already used in high-power electronics (like fast chargers and RF amplifiers). GaN can handle higher voltages and frequencies than silicon in some contexts. While GaN transistors themselves don’t easily scale to 1 nm gate lengths, GaN and related III-V semiconductors might play a role in specialized parts of mining hardware (for example, in power management circuits or high-frequency components). These materials won’t replace silicon for the core logic in ASICs, but they can improve the overall efficiency and performance of the system when used in the right places.

| Material | What It Is | Why It Matters | Potential Impact on Bitcoin Mining | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Cylindrical “rolled-up graphene” structures with near-zero resistance. | Can operate below 1 nm without major tunneling issues; extremely energy-efficient transistors. | Could push ASIC efficiency below 5 J/TH; CNT prototypes already show 1,700× efficiency gains vs silicon in some tasks. | Manufacturing challenges, alignment issues, large-scale production not yet solved. |

| 2D Semiconductors (e.g., MoS₂, WSe₂) | Atom-thin semiconductor layers, only 1–3 atoms thick. | Natural bandgap + ultra-thin channels reduce leakage at ultra-small node sizes (<1 nm). | Potential use in transistor channels for future chips (possibly in the 2030s), enabling cooler, more efficient mining hardware. | Still experimental; integration into mainstream chip fabrication is complex. |

| Graphene | One-atom-thick sheet of carbon with extreme conductivity and strength. | Superb electrical performance; excellent candidate for interconnects or high-speed pathways. | Could improve speed and thermal management in ASICs (not the transistor itself). May be used in interconnect layers. | Pure graphene has no bandgap, so it cannot function as a transistor (can’t switch off). |

| Graphene Derivatives (e.g., Graphene Nanoribbons) | Narrow graphene strips engineered to introduce a bandgap. | Adds switching capability while retaining graphene’s electrical benefits. | Possible use in specialized chip components where ultra-fast conduction is needed. | Fabrication precision is extremely difficult at scale. |

| Gallium Nitride (GaN) | High-mobility semiconductor used in power electronics and high-frequency devices. | Handles high voltages, heat, and switching frequencies better than silicon. | Useful for power management circuits, voltage regulators, high-frequency parts of mining hardware. | Not suitable for core logic transistors; cannot scale near 1 nm. |

| Other III-V Materials (InGaAs, GaAs, etc.) | Semiconductors with high electron mobility. | Useful for high-speed analog or RF components. | May increase ASIC efficiency in communication or signal layers of miner design. | Not suitable replacements for silicon for digital logic. |

In summary, the silicon era of “smaller is better” is nearing its sunset. But a new dawn with exotic materials is on the horizon. The transition won’t happen overnight – integrating new materials into mass production is a huge challenge (there are issues of cost, fabrication techniques, reliability, etc.). Still, the promise of new materials is that they could take us beyond the roadblock that silicon presents. I’m personally thrilled by the prospect; it means the innovation in mining hardware won’t stop at 1 nm. Instead, it might just shift to a new playing field with novel physics. As someone deeply invested in mining technology, I’ll be keeping a close eye on these breakthroughs – they could redefine what our ASICs look like in a decade’s time.

How Could Quantum Computing Eventually Impact Bitcoin Mining?

I get asked if quantum computers will render mining rigs obsolete. The idea of a quantum machine instantly solving Bitcoin’s puzzles sounds like science fiction. How might quantum tech intersect with mining?

A quantum computer could speed up Bitcoin mining, but only to a limited extent. Grover’s algorithm offers at best a square-root reduction in hashing difficulty, not an exponential leap. In practice, no quantum mining device exists yet at anywhere near the scale needed to outperform classical ASICs.

When people hear “quantum computing,” it evokes images of super-powerful machines cracking codes in an eye-blink. It’s natural to wonder: would a quantum computer make all our mining hardware obsolete by finding hashes dramatically faster? The short answer – at least with our current understanding – is no, not anytime soon.

The main theoretical approach to use quantum computing for mining would involve Grover’s Algorithm. Grover’s algorithm can provide a quadratic speed-up for brute-force search problems. Mining Bitcoin (finding a SHA-256 hash below a target) is essentially a brute-force search. In classical terms, miners must perform on average 2^256 hash computations to find a valid block (since SHA-256 outputs 256-bit values). A quantum computer running Grover’s algorithm could cut this effort to roughly 2^128 operations. That’s the square-root reduction in complexity – which sounds huge, and it is a big theoretical improvement, but note: 2^128 is still an astronomically large number. It’s about 3.4×10^38, so even halved, the search space remains enormous.

To illustrate, imagine today’s fastest ASIC miner, and imagine a hypothetical quantum miner that uses Grover’s algorithm. If both have the same energy and hardware constraints, the quantum miner might end up being potentially twice as fast at finding a block as the classical miner (since searching 2^128 space vs 2^256 is like doing half the work exponent-wise). A 2x speedup is nothing to scoff at, but it’s a far cry from the kind of exponential speedup people might fear. Bitcoin’s proof-of-work is specifically designed to be resistant to drastic speedups – there’s no known algorithm (quantum or otherwise) that can do exponentially better than brute force in finding SHA-256 preimages.

Now, let’s talk reality: Do such quantum miners exist? No. The quantum computers that exist in labs today have on the order of 50 to a few hundred qubits. To run Grover’s algorithm for something as complex as Bitcoin’s mining puzzle, you would need a fault-tolerant quantum computer with millions of stable qubits. One estimate suggests we are “about 1 million qubits away” from just the beginning of practical quantum applications, and on the order of 13 million qubits to threaten current cryptography. We are nowhere near that scale — current devices are noisy and decohere quickly, and each additional qubit makes the system exponentially harder to maintain. In other words, a useful quantum computer for mining is a theoretical concept for the foreseeable future.

Even if, say a decade or two from now, someone built a quantum computer that could give that Grover’s quadratic speedup for mining, the impact on the Bitcoin network might still be limited. Here’s why:

- Network Difficulty Adjustment: Bitcoin is designed to adjust the mining difficulty every 2,016 blocks (~ every two weeks) to target a constant 10-minute block time. If a subset of miners (even quantum ones) start finding blocks faster, the network will simply raise the difficulty. So a moderate speed advantage from quantum hardware would be temporary; the system self-corrects to level the playing field. In practical terms, a quantum miner that’s twice as fast as conventional miners could enjoy a larger share of block rewards for a brief period, but by the next difficulty retarget the advantage would shrink.

- Mass Adoption vs. Niche Use: To truly “beat” classical ASICs, quantum mining rigs would need to be widely available or one entity would need to have an overwhelming majority of them. If just one or a few parties had fast quantum miners, they might mine a disproportionate number of blocks until difficulty catches up. However, achieving and maintaining a 51% hash rate advantage with any tech (quantum or not) is extremely difficult and expensive. And if it did happen, it would likely alarm the community and potentially invite countermeasures (like changes to the PoW algorithm).

- Other Bottlenecks: Mining isn’t just about pure computation; there are energy and cost considerations. Quantum computers currently require very specialized conditions (like dilution refrigerators at millikelvin temperatures) and enormous overhead to keep qubits stable. The energy per operation is not actually “free” or even low – controlling quantum hardware can be more energy-intensive per operation than a tuned ASIC, especially when error-correction is accounted for. So even if the math says fewer operations are needed, the real-world efficiency might not favor quantum machines for something like hashing.

- Security vs. Mining: It’s worth noting that quantum computers pose a bigger potential threat to Bitcoin on the cryptography side (like breaking ECDSA signatures to steal coins) than on the mining side. The Bitcoin community is aware of this, and there are already ideas and even test implementations of quantum-resistant cryptographic algorithms for the network if it ever becomes necessary. For mining specifically, the community could similarly agree to change the proof-of-work function to one that’s less amenable to quantum speedup (or simply incorporate larger output hashes, etc.) if quantum miners started to become a realistic issue. In essence, Bitcoin can adapt to quantum advancements when needed, and it likely will long before quantum mining becomes a thing.

| Topic | Key Points |

|---|---|

| 1. Network Difficulty Adjustment | • Bitcoin adjusts difficulty every ~2,016 blocks (~2 weeks). • If quantum miners find blocks faster, difficulty rises automatically. • Any speed advantage is temporary; the network self-corrects. |

| 2. Impact of Partial Quantum Adoption | • A few quantum miners could get a temporary increase in block rewards. • To dominate long-term, quantum rigs would need massive market share. • Sustaining >51% hash power is extremely expensive and unlikely. • Community would intervene if block production became unbalanced. |

| 3. Real-World Bottlenecks of Quantum Mining | • Quantum computers require extreme cooling (millikelvin) and expensive equipment. • Large energy overhead for qubit control and error correction. • Real-world energy per operation may be higher than ASICs. • Practical quantum miners are far from being energy-efficient hashers. |

| 4. Security Risks vs. Mining Risks | • Quantum machines pose larger threats to Bitcoin’s cryptography (e.g., breaking ECDSA signatures). • Mining is less vulnerable due to difficulty adjustment. • The community is already researching quantum-resistant signatures. • Bitcoin can update PoW or cryptographic schemes if needed. |

| 5. Community Adaptability | • Developers can change PoW to a quantum-resistant algorithm. • Hash sizes or structures could be modified to limit quantum advantage. • Bitcoin’s protocol can evolve before quantum miners ever dominate. |

Contact MinerSource Purchase Your Mining Rig Now

In conclusion, quantum computing is a fascinating technology, but its eventual impact on Bitcoin mining appears limited and distant. For now, dedicated ASICs remain the undisputed kings of proof-of-work. I’m personally not losing sleep over quantum mining yet – my focus remains on the tangible tech and upgrades we can deploy today. If and when quantum breakthroughs come, I expect we’ll have plenty of warning and a suite of defenses or adjustments ready in the Bitcoin protocol. Until then, the ASIC upgrade cycle and silicon innovations (and soon new materials) are what keep the mining world turning.

How Can Miners Stay Ahead of the Curve with Upgrade Cycles?

In mining, a well-timed upgrade can make or break your operation. I’ve seen farms thrive by adopting new machines early, and others falter by clinging to aging rigs for too long.

Miners stay ahead by planning regular hardware refreshes aligned with new chip generation releases. Upgrading to more efficient ASICs at the right time maintains a competitive hashrate and lower power costs, ensuring operations don’t fall behind.

For anyone running a mining operation, one of the biggest challenges is knowing when to upgrade your hardware. Wait too long, and your older miners start falling behind in efficiency – they produce fewer hashes for the same electricity, eating into profits. Upgrade too often, and you might overspend or never fully pay off the gear before replacing it. I’ve personally had to make these tough decisions; for instance, a few years ago I debated whether to retire our fleet of Antminer S9 units (which were workhorses on 16 nm chips) in favor of the then-new S19 generation. It wasn’t an easy call – every upgrade is a big capital expense – but once the numbers showed the S9s were nearing unprofitability after a Bitcoin halving, the choice became clear.

Staying ahead of the curve means anticipating technology cycles and financial cycles. Here are some key considerations I use when planning upgrade cycles:

- Efficiency Gains vs. Power Costs: Newer ASIC models typically deliver significantly better efficiency. For example, as of 2025, top-of-the-line miners achieve ~15–20 J/TH, whereas older models (like the Antminer S19 from a few years back) were over 100 J/TH. This huge gap means modern gear can hash six to seven times more on the same electricity. If you pay, say, $0.05 per kWh for power, running an outdated miner can erode or eliminate your profit margin. Upgrading ensures you’re getting the most hashes per watt and keeps your electric costs per Bitcoin as low as possible. Always calculate how much revenue per day per machine vs. electricity cost per day – if an upgrade cuts power use by 50% for the same output, that directly doubles your potential profit margin (all else equal).

- Network Difficulty and Hashrate Growth: Bitcoin’s network hash rate tends to trend upward over time (with some plateaus and dips, especially tied to the market price). When many miners upgrade to new hardware, the total hashpower jumps, and the difficulty adjusts upward accordingly. If you sit on old hardware during such surges, your slice of the pie (the probability of finding blocks) drops dramatically. Essentially, even if your machines keep running, they might become a negligible fraction of the network. To stay competitive, you often need to upgrade around the times others are upgrading, or even slightly before. It’s a bit of an arms race. I keep an eye on announcements from major manufacturers (Bitmain, MicroBT, Canaan, etc.) and on the global hash rate trends. If I see a big wave of new machines coming (for example, a lot of pre-orders for a new 3nm miner model), I’ll plan for how and when to integrate some of those into our lineup so we’re not left hashing at a disadvantage.

- Halving Cycles: Bitcoin’s block reward halving every four years is a predictable seismic event for miners. After a halving, revenues (BTC earned per block) are cut in half instantly. If the price of Bitcoin doesn’t double overnight (it usually doesn’t, at least not immediately), mining profitability plummets for a while. In these moments, only the most efficient miners remain solidly profitable. Those running older, power-hungry equipment often see their profit margins evaporate or even turn into losses once the halving hits. Many had to shut off machines like the S9 after the 2020 halving, for example, because they just couldn’t pay for themselves at the new reward level. A smart strategy is to time major upgrades before a halving. That way, when the halving comes, you have the latest tech with the best efficiency working for you. It’s not unlike how companies might upgrade fleets of vehicles to more fuel-efficient models before a long-term rise in fuel prices – you prepare in advance for the squeeze. In my case, I made sure to have next-gen units in place ahead of the 2024 halving, knowing competition would get fiercer afterwards. It paid off, as running efficient 5nm/3nm miners helped weather the reduced rewards while some competitors with older gear had to scale down or merge operations.

- Return on Investment (ROI) and Timing: Every upgrade should be analyzed like any other investment. How many days or months of mining (at current difficulty and price) will it take for the new machine to “pay for itself”? This ROI calculation depends on the cost of the hardware, your electricity rate, and the miner’s efficiency. Generally, deploying a new generation early in its lifecycle yields a longer period of top-tier profitability. If you wait too long to buy, you might save money on purchase price as hardware gets cheaper, but you also miss out on months of better performance. I try to strike a balance: I don’t necessarily jump on day one of a new miner release (prices can be very high initially), but I also won’t wait until everyone has it. Another factor is resale value of old equipment – selling your used miners while they still have some market value can offset the cost of new ones. I’ve funded part of upgrades by offloading last-gen machines to smaller or hobbyist miners (who might have cheaper electricity or other reasons to buy older gear). Timing the resale right before a major performance cliff (like a halving or before a flood of used gear hits the market) maximizes what you recoup.

- Infrastructure and Logistics: Finally, consider that new equipment might come with new requirements. New miners might draw more power per unit (even if more efficient, they might pack more hashboards). Ensure your facility’s power distribution, cooling systems, and physical space can handle the upgrade. For instance, if you plan to switch to some of the latest hydro-cooled ASICs, you need the plumbing and cooling infrastructure ready. In my case, when preparing for the newest generation, I had to upgrade some of our electrical circuits and cooling setups in our Shenzhen warehouse, because the density of the new rigs was higher (watts per rack). Staying ahead means not just buying the boxes, but also upgrading the supporting environment proactively. Downtime is costly, so I align facility improvements with hardware upgrade cycles to minimize any interruptions.

| Factor | What It Means | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Efficiency Gains vs. Power Costs | New ASICs reach 15–20 J/TH, old models (e.g., S19) exceed 100 J/TH. | Modern miners produce 6–7× more hashrate per watt, dramatically reducing daily electricity cost and speeding up ROI. |

| 2. Network Difficulty & Global Hashrate Growth | Difficulty rises as more miners upgrade and hashpower increases. | Old rigs earn a smaller % of block rewards, becoming uncompetitive. Staying updated maintains your share of the network. |

| 3. Halving Cycles | Block rewards drop 50% every 4 years. | After halving, only efficient miners stay profitable. Upgrading before a halving protects your operation from revenue shocks. |

| 4. ROI & Upgrade Timing | ROI = hardware cost ÷ daily net profit. | Early adopters of new-gen miners enjoy longer peak-profit windows. Smart resale of old rigs helps reduce upgrade cost. |

| 5. Infrastructure & Logistics | New hardware may require extra power capacity, cooling, hydro setups, or space. | Preparing the facility early avoids downtime. Strong infrastructure lets you run higher-density, next-gen miners smoothly. |

Staying ahead of the curve is both an art and a science. It requires watching technical trends (like chip roadmaps) and economic signals (like Bitcoin price trends and mining difficulty projections). I regularly communicate with our large clients – some of them operate mining farms in North America and Europe – about their upgrade plans, and often we coordinate orders for new devices together. Being a step ahead in placing orders can be crucial, as supply shortages for the latest miners are common (everyone wants the new unit right away). At Miner Source, with our Hong Kong and Shenzhen warehouses, I make it a point to always have a pipeline of the latest machines ready for our clients, whether they are large institutional miners or enthusiasts scaling up. By staying nimble and planning ahead, we help our customers (and ourselves) navigate the ever-changing landscape of mining profitability.

Ultimately, the key philosophy is: never get too comfortable with your current setup. The mining world is one of constant evolution. Those who plan for and embrace the change will continue to thrive. Those who don’t… well, I’ve seen once-successful mining operations go under because they skipped one upgrade cycle too many in an increasingly competitive environment. My approach is to continually assess and ask, “what’s the next tweak or upgrade that will keep me competitive?” If you’re always asking that, you’ll rarely fall behind.

Conclusion

Chips beyond 2nm, new materials, and even quantum tech will shape Bitcoin mining’s future. I’m determined to keep Miner Source—and our clients—ready for whatever comes. Contact MinerSource Purchase Your Mining Rig Now